Bristlecone Pines, Manzanar, and the Alabama Hills: Beauty in the Face of Adversity

In a span of three days I hiked amongst ancient Bristlecone Pines, toured Manzanar (a former Japanese internment camp), and explored the Alabama Hills. Visiting one right after the other naturally led to comparisons, and I was struck by their common thread: Beauty - and even triumph - in the face of extreme adversity.

Great Basin Bristlecone Pines

To see these ancient bad-boys, my friend Karen and I drove to the Schulman Grove Visitor Center off of White Mountain Road, about 24 miles from Big Pine. I thought I’d be blown away to be in the presence of some of the oldest living things on earth, but the scraggly trees and drab, dusty environment were underwhelming - at first. This is a place to stay awhile, walk amongst the trees, and learn a thing or two.

The grove is named after Dr. Edmund Schulman for his contributions to dendrochronology (the science of dating events using tree growth rings). In the 1950s, Schulman discovered and named Methuselah, what was then the oldest known “non-clonal organism” in the world at 4,848 years old. In 1962, Don Currey gained the dubious distinction of discovering the next oldest Great Basin Bristlecone Pine - after he cut it down. A Radiolab podcast dives deep into Don’s somewhat tragic tale (highly recommend). Unfortunately, Don didn’t live to see the discovery of an even older tree in 2012, dated at 5,066 years old.

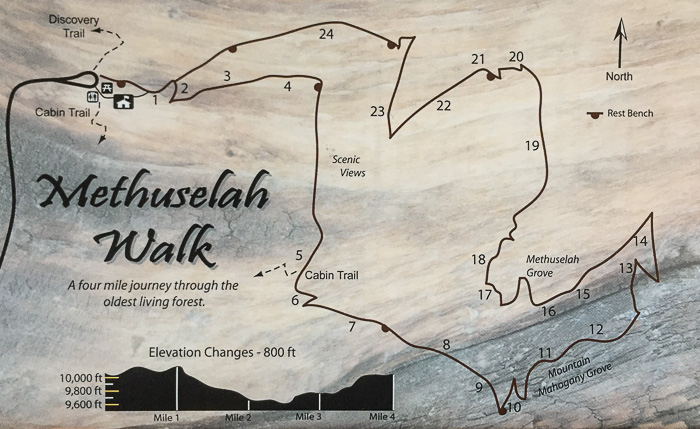

At the Schulman Grove, there are numerous ways to learn about these unique, hardy trees: watch the movie in the visitor center, read helpful signs and displays, or take a walk on the Discovery Trail (1 mile) or the Bristlecone Cabin Trail (3.5 miles). If you have the time and energy, though, pick up an interpretive guide at the trailhead and hike the Methuselah Trail.

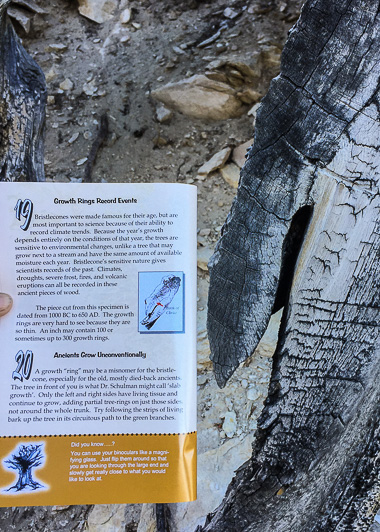

This 4.2-mile trail has 24 numbered stops, each highlighting a point along a Bristlecone Pine’s journey “from seed to snag.” It’s a moderately strenuous hike considering the elevation (~10,000 feet) and 800-foot gain, but fascinating and well worth the effort. When we hiked I appreciated the slow reveal of facts, each bite-sized nugget of information accompanied by a real-world example, and gradually fell in love with the colors, shapes, and twisted beauty of trees sculpted by extreme wind and weather over thousands of years.

So why do the Great Basin Bristlecone Pines have such longevity? The oldest of the old have adapted to their harsh environment, and survive because of the difficult conditions. In fact, one sign revealed “Bristlecones that take root in better soils with more moisture often grow faster and taller, but die at much younger ages.”

The Great Bristlecones only grow at elevation in the mountains of Nevada, Utah and Eastern California where it’s dry, cold and windy. With a short growing season, trees can grow just an inch in 100 years which produces dense, pest-resistant wood. They also manage to thrive in soil that’s too harsh for other plant life, resulting in little undergrowth (which limits the spread of wildfires) and little competition for nutrients and water. They’ve made myriad survival adaptations, each one saving energy or securing precious nutrients. It’s a tough life and a struggle to survive, but they are hardier for their difficult environment. Life lesson?

Website: Schulman Grove Visitor Center

Location: Off of White Mountain Road, 24 miles from Big Pine, CA

Cost: Day use fee of $3/person, or maximum of $6/car. $1 to purchase the Methuselah Walk guide, or borrow a copy and return it when done.

Hours: The visitor center is seasonal, so check the website for hours and closures. Summer hours are generally 10am–5pm daily. We visited on a Wednesday in mid-October when it was only open Friday through Monday, so couldn’t see the center or watch their overview movie. Next time!

Manzanar National Historic Site

In my book, this is a must-see. It is important - now more than ever - to reflect on this dark time in American history and to learn from past mistakes. From the Visitor Center:

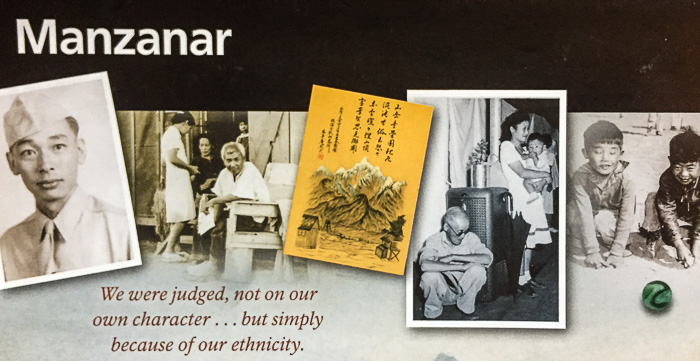

In 1942, the United States government ordered over 100,000 men, women, and children to leave their homes and detained them in remote, military-style camps. Two-thirds of them were born in America. Not one was convicted of espionage or sabotage. For 10,000 of them, Manzanar would be their new home.

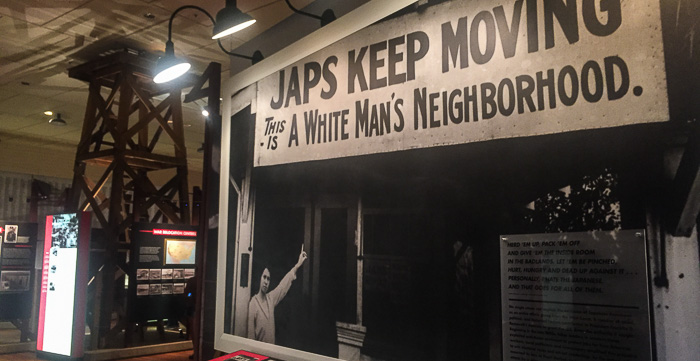

How did this happen? One commission cited “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.” The Manzanar museum sets the stage by describing anti-Asian sentiments in the U.S. in the years leading up to World War II. The bombing of Pearl Harbor added fuel to the fire and led to Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin Roosevelt, which gave the Secretary of War the power to designate military zones and decreed that "...the right of any person to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may impose in his discretion." This allowed for internment of Americans with German ancestry (11,000), Italian ancestry (3,000), and some Jewish refugees. By far the largest targeted group were those of Japanese ancestry (up to 120,000 according to Wikipedia). Again, from a display:

Not all politicians and military leaders doubted the loyalty of Japanese Americans. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover found no “factual data” which justified the mass relocation. Attorney General Francis Biddle believed this action clearly violated the U.S. Constitution. Nevertheless, the War Department prevailed.

It was heartbreaking to learn that many Japanese went willingly, trusting in the U.S. Government and believing compliance to be the best way to ease tensions. Little did they know how long their interment (incarceration) would last. For over 3 1/2 years, the Japanese detained at Manzanar endured meager, restricted, crowded conditions in a desolate stretch of desert with extreme temperatures and driving winds that relentlessly deposited sand in every nook and cranny. Matsue Nishimori Watanabe noted “…you’re just in shock because you had never lived like that before…but when you’re there…you just adapt yourself to the conditions you’re in. And they’re not pleasant conditions, but there isn’t anything else you can do…”

The movie and museum give a sense of life and struggle in camp, but the reconstructed Block 14 barracks and mess hall offer a chance to walk into history and hear first-person accounts. Throughout our visit, I was most touched by the detainee’s ability to make order from chaos, and create beauty in the face of such ugliness; the gardens are the most obvious example. Block 22 Garden was one of the first and was informally known as Three Sack Pond since landscaping projects were limited to three sacks of cement per month per block. That project inspired internees in other blocks, and today, Manzanar has remnants of 10 gardens spread throughout the camp’s 36 blocks.

Merritt Park, the largest garden at 1.5 acres, was created by landscape designer Kuichiro Nishi. He and fellow internees built paths, bridges, and flower gardens that transformed the desert into a serene escape for the community. Today, only echoes remain of the oasis that once was.

By the time the camp closed in November 1945, 150 men, women, and children had died at Manzanar. The cemetery’s monument “The Soul Consoling Tower” is a permanent tribute to those who died; it's also the destination of an annual pilgrimage, first started in 1969 and now held the last Saturday of April each year. The 2017 pilgrimage literature beseeches:

Never again, to anyone, anywhere!

Yes, never again. And yet we face a chillingly similar situation today with Executive Order 13769: prejudice, hysteria, failure of political leadership, and a sweeping Executive Order that has no basis in fact and was opposed by the acting Attorney General and our federal courts. A travel ban based on a person's religion isn't right. It should not stand.

Here’s a little more about life at Manzanar. If you’re in the area, visit.

Website: Manzanar National Historic Site

Location: Off of Route 395, 10 miles north of Lone Pine, CA

Cost: Free

Hours: The Visitor Center has seasonal hours; check here for updated information. Summer hours are generally 9am–5:30pm daily.

The Alabama Hills

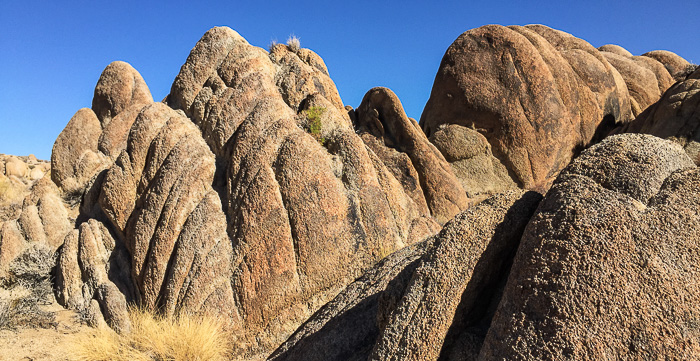

Driving Route 395, we didn’t see the point in visiting the Alabama Hills; they looked like plain old hills, nothing special. Turns out, we were looking at the wrong hills! The Alabama Hills lie behind those plain-Jane hills and man-oh-man are they cool! Once in the correct area, I immediately guessed that the Galaxy Quest rock monster scene was filmed here. Nope, wrong again; that was in Utah’s Goblin Valley State Park, but plenty of other movies were filmed in this crazy landscape.

As this article explains, violent earthquakes formed the Sierra Mountains which have a unique rain shadow on the eastern (windward) side. The surreal rounded rocks and arches of the Alabama Hills were formed over millions of years of erosion and spheroidal weathering.

To explore the area, head to Lone Pine (on Route 395) and then take Whitney Portal Road to Movie Flat Road. This dirt road winds north through the Alabama Hills, and is passable for most cars. Stay on the main road, though - side roads can be rougher and require high clearance or 4-wheel drive. Walking is easy in these gentle hills, and Shark Fin and Mobius Arch are two popular trails. This map shows general locations for other arches, but it may take some wandering to find them. Karen and I had a delightful desert jaunt searching for the Whitney Portal Arch, but never managed to locate it!

If you’re a fan of Westerns, stop by the Museum of Western Film History ($5 donation/adult) or take their self-guided driving tour of 10 movie locations set in the Alabama Hills (free online). Many visitors recommend the museum as a must-see stop before exploring the hills.

Finally: How did the area get its name? Prospectors in the 1860s named numerous mining claims after the Confederate warship, the CSS Alabama. The name stuck.

Website: Alabama Hills

Location: Enter at the intersection of Whitney Portal Road and Movie Flat Road, 2.5 miles west of Lone Pine, CA.

Cost: Free

Hours: Open (not gated)

This article is one of many written about a 3-week road trip spent hiking and camping in the Eastern Sierras and Death Valley. To see all articles, check out this trip summary.