The Other Las Vegas Part 3: Hoover Dam

We had seven glorious days to explore Las Vegas which allowed ample time to see new sights while also visiting an old favorite. Chris and I hadn’t seen Hoover Dam in years so a visit was high on our list. Before we could reserve a general tour online, connections within our multi-state syndicate kicked in and set up a private tour. Know what I’m talkin’ about? Connections. I hadda friend who hadda brother who knew a guy. Ha! Yes, I visited the Mob Museum. It changed me friends, it changed me.

Back to Hoover Dam.

i love this place so much i can hardly contain myself. Admirable restraint, right? No all-caps or exclamation points, even though well-deserved. To quote Franklin Delano Roosevelt, "This morning I came, I saw, and I was conquered as everyone will be who sees for the first time this great feat of mankind."

I enjoy traveling for the opportunity to see and learn, and recent trips have been enhanced by brushing up before-hand with a good book or two. I struggled to choose a book for Vegas but once Hoover Dam was added to the itinerary, I checked out a library copy of Hoover Dam: An American Adventure by Joseph Stevens. Love it! Stevens captures the awesome scale and scope of dam construction while also providing details of harrowing conditions and unbelievable feats. He also has a flair for describing characters, from simple laborers to the visionary, gutsy businessmen and engineers who had the gumption to tame the mighty Colorado. If a dam book is too much to tackle, a bunch of dam documentaries are available online. Dam jokes…they never get old :D

Hoover Dam’s history has so many interesting stories and gripping facts, they bubbled up out of me in a steady stream. I think Chris grew desperate for me to finish my book, visit the dam, and move on, although out loud he said he appreciated the info.

- Boulder Dam or Hoover Dam? Both! Although construction began in 1931, planning began in earnest a decade before. Boulder Canyon was long considered the better location and the moniker stuck even after Black Canyon was selected. To confuse matters further, the name was dedicated to Hoover in 1930, changed back to Boulder Dam in 1933 after Hoover lost to Roosevelt, and re-dedicated to Hoover in 1947 by Congressional resolution. Whew.

- Portland connections: The project was too big for one company to finance, and the Six Companies consortium included folks from Portland, Oregon including Charlie Shea, “a stumpy, profane, cigar-chomping Irishman” who was the biggest builder of tunnels and sewers on the west coast, and Swigart and Hart from the Pacific Bridge Company who installed the piers for the first bridge over the Willamette River. Go Portland!

- Deplorable conditions: The nation was in the grips of the Great Depression, an emergency so acute that President Hoover ordered dam work to begin six months earlier than planned to ensure much-needed jobs and wages. Indeed thousands had already streamed to Las Vegas desperate for work, giving rise to ramshackle desert camps and shanty towns like Ragtown and McKeeversville. Las Vegas soup kitchens were overwhelmed and open spaces were “…so full of sleeping men at night it looked like a battlefield.” The relatively few workers employed in the early phases to build railroads, roadbeds and diversion tunnels (to carry the Colorado around the actual dam site) were housed in stifling temporary barracks with no showers, no electric lights, a 3-seat toilet pit for 480 men, and an open water tank that grew so hot, the water was undrinkable. The living quarters later constructed were cheap and simple but seemed lavish in comparison.

- Unimaginable heat: Construction occurred at a furious pace from the get-go for multiple reasons: Six Companies needed to divert the Colorado by October 1, 1933 or would pay fines of $3,000 for each day over the deadline; engineers were desperate to work while the river ran low; and crews in each of the 4 diversion tunnels were fiercely competitive with each other, trying to tunnel the most in a shift (reportedly 256 linear feet in 24 hours - through volcanic rock!) or be the first to finish outright. They worked relentlessly through searing summer heat and men collapsed regularly, some with body temperatures as high as 112 degrees.

- Staggering numbers: The four diversion tunnels, blasted out of sheer canyon walls on either side of the river, were each 56 feet in diameter and had a combined length of over 3 miles. On the dam itself, work grew so efficient that men were dumping 1,100 buckets of concrete a day at a rate of one every 78 seconds. There’s enough concrete in the dam to pave a two-lane highway from San Francisco to New York. And no, contrary to popular lore, nobody was actually buried in the dam. Concrete pours were too shallow and had a person actually fallen in, their body would be a threat to structural integrity and would have been removed.

- Acrobatic feats: Fearless “high scalers” dangled on ropes and used jackhammers to strip all debris from the canyon walls. One crazy scaler named Louis Fagan once shifted an entire crew from one site to another while at the end of a 200-foot rope. One at a time, men would clamp onto Fagan monkey-style, he’d kick off, and they’d swing out like a pendulum 100 feet around a cliff. Incidentally, these high scalers apparently invented hard hats. They were pummeled with so much falling (and potentially fatal) debris, they resorted to wearing baseball caps repeatedly dipped in tar. Once dry, they had “hardboiled hats” for protection.

- A boon for Block 16: Dam workers lived on the Boulder Canyon Project Reservation (later to become Boulder City) which was a model of temperance, but Las Vegas was just 25 miles away with its drinking, gambling, and the red light district known as Block 16. Thousands of men regularly collected wages and immediately spent them in the city. Some actually paid prostitutes in company scrip (acceptable since women could travel to Boulder and shop on the reservation), but others used their ID badges as currency, telling the women they could be redeemed for $2 each. As expected, this scheme worked only until the first woman attempted to redeem her badges.

- Safety vs. profits: Six Companies is rightfully applauded for their ingenuity, exacting standards, and efficiency, finishing the project two years ahead of schedule and under budget, but they also had a dark side driven by profits. Most notably, they paid workers in company scrip (forcing them to shop in company-owed stores), repeatedly and ruthlessly squashed union efforts, and ignored state mining laws creating hazardous work conditions. Carbon monoxide poisoning was widespread due to the use of gasoline trucks in diversion tunnels, a blatant violation of worker safety. Incredibly, company doctors routinely diagnosed all such cases as “pneumonia”. When workers sued, the company resorted to witness intimidation and tampering with the jury; cases piled up and they eventually settled.

- Official death toll: Numbers vary but most agree that 96 men died during the construction of Hoover Dam. This number is highly suspect as it includes only "industrial fatalities" where men were killed on-site by blasting, falling rock, being hit by equipment, etc. It does not include any off-site deaths (for example, if someone was injured on-site but later died in the hospital) or work-related deaths from heat or "pneumonia."

- Cruel twist of fate: J.G. Tierney was a member of one of the early drilling crews that surveyed Boulder and Black Canyons. He was considered the second fatality of the Boulder Canyon Project when he died on December 20, 1922, after being swept off a barge. Tierney's son Patrick became last man to die during construction of Hoover Dam when he fell from an intake tower on December 20, 1935, exactly thirteen years after his father's death.

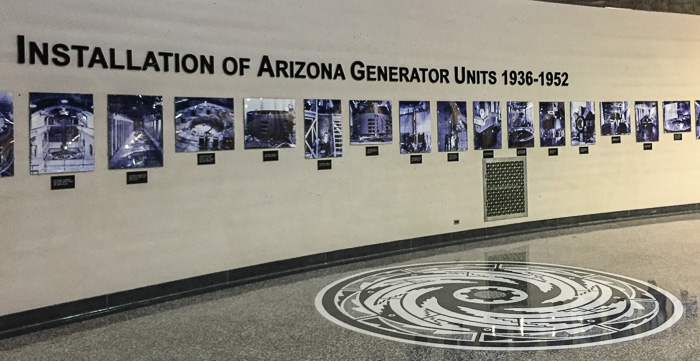

Oh boy. There’s so much more, but I’ve run on long enough and haven’t even gotten to the tour. To read about the dam is one thing, but to see it another. To start, it’s beautiful outside and in. The design is simple Art Deco with original aluminum light fixtures, railings, and doors (whole doors made of aluminum!), and terrazzo floors with Native American inspired mosaics. After stepping off the elevator, we walked hundreds of feet before I realized we weren’t walking across the length of the dam (across the river) but through the width (along the flow of the river). The dam is wedge-shaped, 660 feet thick at it’s base, tapering to 45 feet at the top.

As we walked and ogled, our guide casually explained the basics of power generation to help us understand the function of penstocks (pipes which funnel water in), turbines, etc. Chris later commented that although he majored in electrical engineering, this world of AC power generation is fascinating and foreign. It’s also an interesting juxtaposition of we small humans working on a massive scale, using relatively simple technology writ large. In all the years that our guide worked at the dam, he has noted just two small design flaws. First, the generators were set too close together. When equipment is replaced, heavy ungainly parts must be carefully angled into place. And second,…we forgot to ask about the second (forehead slap!).

When viewing the penstocks, we learned that dam workers have been fighting quagga mussels since 2007. The mussels grow rampantly in one part of the pipe system where water speed is juuuust right, clogging water lines and forcing operators to temporarily shut down turbines that supply electricity to over a million people. I laughed as Chris and I nodded knowingly and shook our heads in sympathy. Yup, mussels. We’ve got zebra mussels at Keuka Lake so we totally know what you’re dealing with. We have to, you know, wear water shoes so our feet don’t get cut, and pull our motorboat really high out of the water so mussels don’t latch onto the prop. We feel your pain Hoover Dam.

Our tour lasted two fabulous hours and was a highlight of our whole Las Vegas adventure. A huge thank you to all the connections who made it possible. We owe you and promise to repay in kind. Please don’t bust our kneecaps.

If you’re in Vegas, do yourself a favor and head out to the dam. Do a simple drive-by along the top of the dam, walk along Memorial Bridge for a spectacular full-face view of the downstream side, stop into the visitor center for an overview of dam construction and operation, or take a tour and descend hundreds of feet to walk inside this concrete monument to man’s audacity. It’s bound to impress no matter which option you choose.

Website: usbr.gov/lc/hooverdam

Location: No street address! GPS: 36.016222, –114.737245

Hours: Visitor center is open 9am–5pm. Parking garage open 8am–5:15pm. Since pedestrians are prohibited from the top of the dam “during hours of darkness”, they recommend arriving by 2pm. Visit their website for further restrictions.

Cost: Drive and look for free. Parking garage $10. Visitor center $10. Powerplant tour (30 min) is $15/adult and includes visitor center admission. Dam tour (1 hour) is $30/adult and includes visitor center admission; no children under 8 permitted; not wheelchair accessible.

Note: For more Vegas articles, refer to the trip summary for the The Other Las Vegas.