The siege is lifted on stroke city aka Derry / Londonderry

I was fairly young and unaware through most of the modern Troubles that rocked Ireland, particularly Belfast and Derry / Londonderry. It wasn’t until I visited here that I even remembered that Derry was the location of Bloody Sunday. Julie and I get the sense that Derry / Londonderry is still getting the short end of tourism, possibly because of its history. This is a shame because we loved our two days here, even though we’ve had our worst weather so far.

Note: I’m just going to say “Derry” because it is shorter to write. One colloqial name for Derry / Londonderry is “stroke city”. Not “slash city”, but “stroke city”. Got it?

If you’ve been following along, you know that I have a direct ancestor, George Walker, that was a big player in the Williamite-Jacobite war in Ireland. There was no shortage of Walker coverage during our Derry visit, though odds are he is not particularly revered by the majority of the Derry population. In fact, the IRA blew up the original monument and don’t seem keen to allow new ones to last.

Why would this happen? I’m going to to recap the last 420 years or so briefly, in my own words, from memory. You can make a good case that the origin of the troubles is right here in Derry.

In the last part of the 1600s, King James II succeeded his brother as the king of England. Despite the recent Protestant reformation in England, James was a devout, converted Catholic. This did not sit well with much of parliament and the nobility, and while James was away (in France I believe) deals were made to bring William of Orange over from the the continent to steal his throne. It should not come as a surprise that William was married to James’ daughter Mary. This coup was known as the Glorious Revolution and was welcomed and bloodless. William was interested in more than the throne: he also wanted to get King Louis XIV off his back in the Dutch region, so having access to British forces would keep a nascent threat right across the channel.

This of course pissed of James, losing his throne and all, and as the rightful king he sought to regain the throne through force. His beachhead would be Ireland for two main reasons: proximity to Ireland and access to more troops by recruiting fellow Catholics in Ireland. The largely Catholic southern part of Ireland welcomed the king and he was easily able to raise a military to augment troops given by France (Louis XIV) and other mercenaries. These Irish forces would be fierce but poorly trained and armed.

James swept through Ireland in 1688–1689 but needed to close off the key strongholds and ports in the north where there was a significant (Protestant) population loyal to William. He was able to do so with one key exception: the walled city of Derry. Right about the time James’ army was marching to Ulster (the northern portion which is now essentially Northern Ireland), orders were sent ahead for Derry to send its Protestant garrison away to Dublin to be replaced by a Catholic garrison. There was much confusion and concern about this order in Derry and the Protestant population there was understandably paranoid. The story is that several young “Apprentice Boys” disobeyed this order and ran to close and lock the gates to the city before the Catholic garrison could enter. This started the standoff in Derry (late 1688) but the siege would officially start in early 1689 with cannons firing both ways as James’ army reached the town and its walls. To support their siege, James also established a blockade of the River Foyle to prevent reinforcements from coming in through the bay off the Atlantic Ocean.

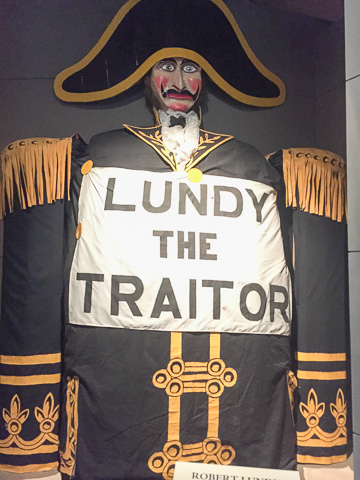

The governor of Derry as this was happening was this guy named Lundy. Lundy was not very optimistic about their chances of withstanding a siege. Lundy, perhaps secretly, attempted to negotiate with the enemy. Was he trying to save his own skin, or was he genuinely concerned about the welfare of the city and trying to save as many people as he could? His attempt was discovered and he was shamed into abandoning his position. My ancestor Rev George Walker was selected along with another (more soldierly) man to assume the Governor role. Walker helped Lundy disguise himself and escape.

Was Lundy a traitor? Ask most Protestants around Derry and they will probably say yes. They’ve burned an effigy of him every year now for centuries, so I’d say they really haven’t chosen to forgive him yet. Our friend Billy that we met in Belfast denies that Lundy was a traitor. With the limited evidence I have, I would agree. He may have been afraid, perhaps even craven, but negotiating a surrender is not necessarily a traitorous act. He is cast in a shadow because Walker helped lead the city through the siege and ultimate rescue. If the siege had worked and city fallen (with likely over 10,000 lives lost), Lundy may have been looked at as the one man who could have saved the people.

So Walker is revered as one of the men who saved the city and is symbolic for the Protestants in Derry as a man who said “Never Surrender” in the face of a Catholic majority. Note that while Walker was a Church of England clergyman, the vast majority of the Protestants in Derry at this time were “non-conforming” Presbyterians. These were mostly plantation settled Scotsmen.

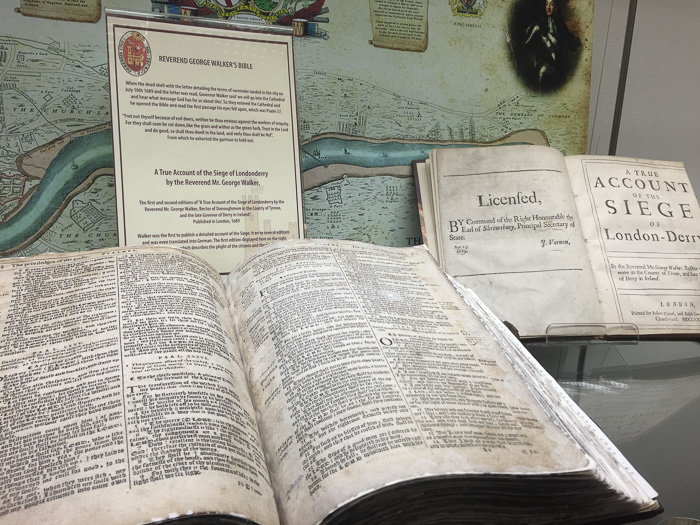

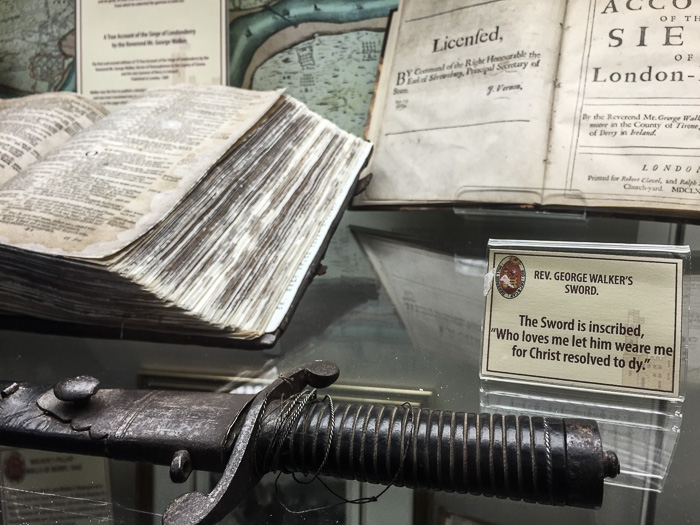

After the siege Walker did a sort of publicity tour in England and spoke to parliament about the siege. They had him write a true account which he soon published. Others wrote their own true accounts of the siege, at times contradicting Walker’s. So he wrote another book, a vindication of his true account. All of this must have happened within about a 9–12 month period because Walker made his way back to Ireland where the James / William issue was far from decided.

William of Orange landed at Carrickfergus (not far from Belfast) with over 30,000 troops, a hodgepodge of regular English troops, Dutch, French Huguenots, and mercenaries just like William had. An interesting side note that the Orange Order in Northern Ireland isn’t always so keen to admit: because the Papacy and King Louis XIV were at odds during this period, the Pope supported William in this operation.

To close out the Jacobite - Williamite War story, William and his forces marched on James and had a pitched battle at the Boyne river near Drogheda. William won and routed James’ forces who mostly escaped but from there it was just mop-up duty for William’s army. This sealed English (and Protestant) dominance in Ireland for the next 300 years.

The home rule movement in Ireland started in earnest in the late 1800s, culminating in the Easter rebellion in the early 1900s and a negotiated independence after WWI with a partitioned Ireland. As eager as the Irish nationalists and republicans where to leave English rule, the Protestant loyalists (largely in Ulster) were fearful of reverting to Catholic rule. These loyalists rose in a sort of counter rebellion to ensure that the UK would not abandon them, and succeeded in negotiating a partitioning out of Ulster from the new Republic of Ireland. There was no perfect way to draw this line (think Gaza or the West Bank in Israel), and a large pocket of Catholics surrounding Derry were brought into the UK and left out of the Republic.

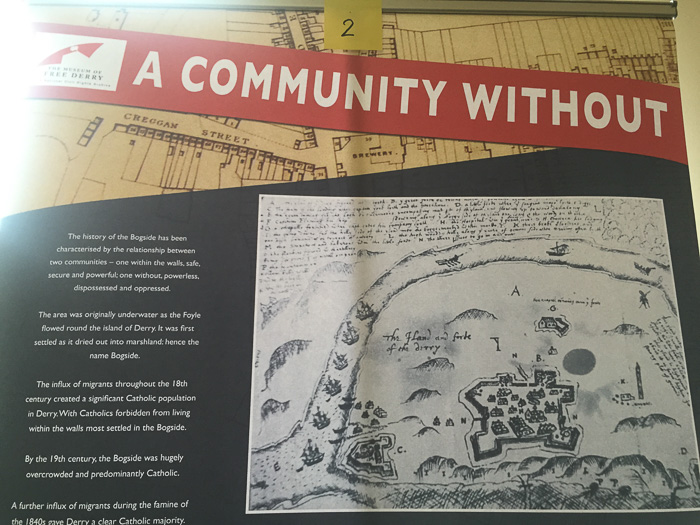

While they may have mostly lived peacefully in Northern Ireland (NI) from the 1920s through the 1960s, by most accounts they were an oppressed minority (though in Derry they were in the majority). Despite the rule of law in England being “one man/woman, one vote”, in NI voting rights were still tied to property ownership. This combined with gerrymandering ensured ongoing Protestant control of the Derry city government and hence the police and other social services.

Inspired by the civil rights movement and marches in the United States, the Catholics in NI began to take to the streets for mostly non violent protests. There was a broad spectrum here, just as there was in the USA at this time: many were committed to peaceful means and protest while some were convinced that they would need to take up arms to achieve their ends. Violent responses from Ulster police forces in 1969 to mostly peaceful protests lead to both a much wider participation in this movement and more people moving towards violent protest. The Irish Republican Army (IRA) went from about a dozen poorly armed, trained, and organized soldiers to a well armed and organized paramilitary force during the following years.

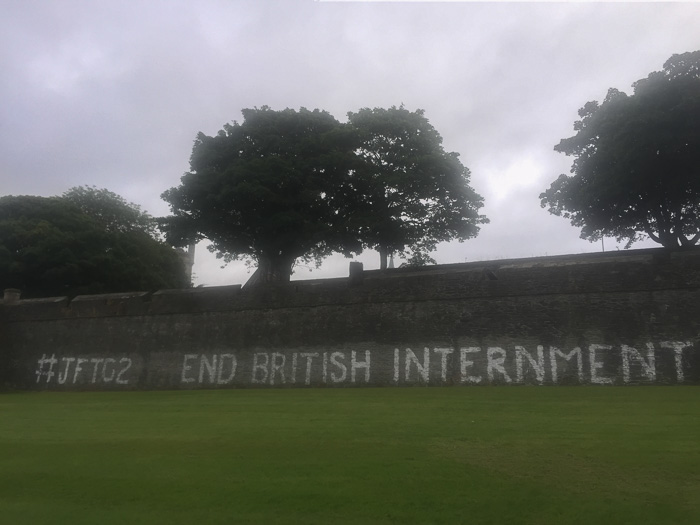

The UK could no longer turn a blind eye to NI and began to intervene. At first this was welcomed by the Catholics as they were hopeful that this would throttle the aggressive stance made by the national and local police. These hopes were gradually eroded then completely dashed in 1972 on Bloody Sunday in Derry in the Catholic Bogside neighborhood when regular British military units opened fire and killed 14 marchers in a protest against internment (jailing without due process) of citizens. The British government in 2010 finally admitted fault after a second inquiry, calling the deaths unjustified and unjustifiable. 1972 was the peak year in terms of violence and deaths during The Troubles, but they would continue on until the 1990s when the Good Friday Agreement brought what appears to be a lasting peace and disarmament of the IRA. Part of this agreement was an allowance of self determination of Northern Ireland to stick around or leave the United Kingdom (remember Scotland’s referendum that almost resulted in them leaving the UK?).

I glossed over quite a bit here and probably missed several key dates and facts, but again it was from memory and I’m not an historian.

So that’s where things stand now. We spent our two days in Derry learning as much as we could from all sides of this history (Church of Ireland, Presbyterian, and Catholic). While we generally found a spirit of reconciliation and desire to move on, there remain undercurrents of blame and fear.

We toured the Derry city walls on our first day and the Bogside area the second day, with each tour being led by a Derry Catholic. While the city wall tour was probably mostly factual, it smelled of propaganda at times because of the delivery and some of the editorial comments made along the way. She commented that the portion of Derry west of the Foyle (“city side”) is 97% Catholic and 3% Protestant, with the 3% living just outside the walls in the Fountain district. There’s another Peace Wall surrounding this neighborhood, so you can bet there’s been ongoing violence between this neighborhood and the surround Catholic neighborhoods. Our guide editorialized that this neighborhood continues to maintain a siege mentality, hearkening back to the siege of Derry, and we took it as a very pejorative comment on this isolated community. We don’t know the whole story, but it seemed out of place in the tour.

The Bogside tour was much more touching and effective. Julie and I were the only two on the tour and got into a cab with the guide and an intern working in the Free Derry museum. Our tour guide was eight years old on Bloody Sunday and lost his brother that day, and has spent most of his adult life working towards a proper accounting of that day. His tour focused on the civil rights origin of the marches in Derry but he never shied away from discussing the violent means taken by some Irish Catholic nationalists. It was a measured but emotional tour. While they’ve achieved so much (most notably the Good Friday Agreement and the Bloody Sunday re-inquiry), Julie and I both had the sense that all is not good. Unemployment remains high in Derry, and there’s been little economic development. Belfast and Dublin seem to be racing ahead and building a modern economy. Derry only recently began to emerge as a tourist destination but I’m sure it lags far behind other popular destinations in greater Ireland.

Julie and I then visited a few displays and museums in the Church of Ireland / Protestant churches within the city walls. We saw many artifacts related to George Walker, including another copy of his famous portrait that greeted us at the Battle of the Boyne center. This was mostly just great historical coverage of the siege, though there’s one element that remains mildly disturbing – in a similar way that the tour guide’s comment about “siege mentality” disturbed us. There’s a men’s association in Derry called the Apprentice Boys, whose sole purpose is to promote recognition and remembrance of the closing of the gates to Derry and subsequent “No Surrender” and failed siege. To join this group you must be Protestant and they have some initiation process that happens within the city. There are branch clubs throughout this part of N.I. While they are not part of the Orange Order, they share similarities and regularly march in Derry. They are the ones that burn the effigy of Lundy every year. It is clear to me that these marches are less about celebrating history than they are a thumbing of the nose to the Catholics. Despite my heritage, I think I’d be just as likely to join the IRA as I would be to join the Apprentice Boys.

The Presbyterians in NI, while certainly on the Protestant side of the table, where also historically second class citizens because of their non-confirming or dissenting status (i.e., not Church of Ireland / England). We had a lovely visit in the First Presbyterian Church within the city walls, including a tour of the Blue Coat School visitor center. A church member kindly stayed with us for the entire visit, telling us stories of the church, the history of members, and even some of the history of Presbyterianism. The church suffered from dry rot that was discovered in the early 2000s, and with contributions from members and even local Catholics they were able to restore the church. The chapel ceiling was restored using white pine from Oregon!

Julie and I both feel that, similarly to Belfast, Derry is a town struggling with its identity and its past. The language is still “us and them” and the communities remain divided. I suppose parallels could be drawn to Ferguson MO or the confederate flag issue in the southern U.S.A. Hopefully education and a new generation can lead to ongoing healing and forgiveness.

We stayed in a great B&B, The Phoenix just outside the Bishop gate. We found very affordable food on the diamond within the city walls, though traditional Irish music was not to be found. Maybe we didn’t stay up late enough.

Finally, to be clear: we loved our visit to Derry and I believe the town is welcoming and the walls are open to visitors. Go to the city with an open mind and discover for yourself the rich and complicated history of Derry / Londonderry.