Hiking Yosemite…and loving it to death?

Yosemite is one of those bucket-list destinations, and I’m eternally grateful that my fist visit occurred late-season - the place was mobbed, even in October! I realize Karen and I did our part to add to the crowds, but sheesh, shouldn’t people be at work or in school or something??

Don’t misunderstand: I fell in love with Yosemite. But while soaking in the grandeur, it was impossible not to see the impact humanity is having on our precious wilderness. It’s not a new issue, as I learned while reading The Last Season by Eric Blehm which tells the story of Randy Morgenson, a dedicated and passionate backcountry ranger who disappeared in the Sierra Nevadas in 1996. From the book:

…the park’s scientists compiled a backcountry management plan in 1960 that outlined ever-increasing populations. They proposed a set of experimental rules and regulations that, if adhered to, would theoretically save the backcountry from becoming another frontcountry. The report read like scripture to Randy, warning of an impending doomsday and often citing his childhood home, Yosemite, as an example of what could occur. Here, in the backcountry of Sequoia and Kings Canyon, man’s presence has not yet dismembered Mother Wilderness - but she was barely hanging on. Armageddon was upon them.

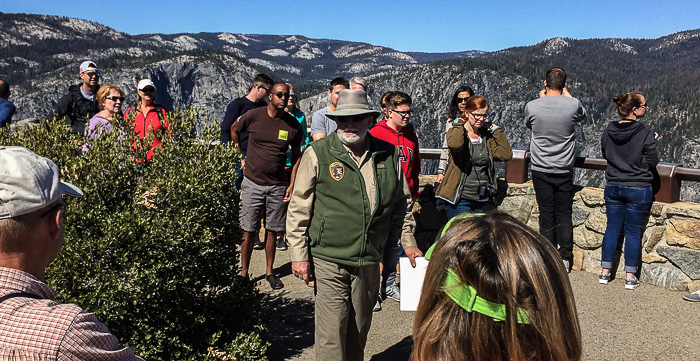

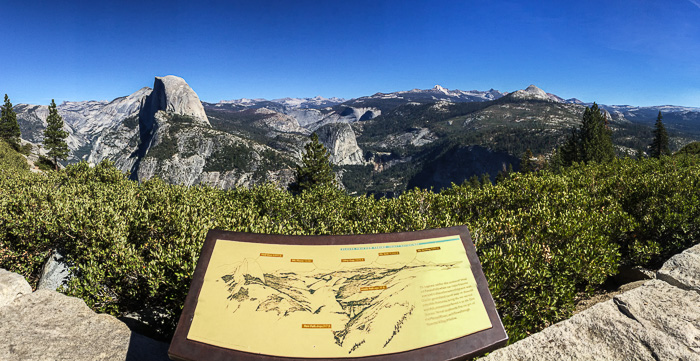

So in 1960, Yosemite was already the poster child for how not to manage our national parks? Incredible! “Armageddon” seems over-stated, but take a weekend jaunt up to Glacier Point and you be the judge. We ended up at Glacier Point twice and while the weekday visit was simply crowded, the weekend stop left me disappointed in my fellow man. The stunning weather brought people up in droves which led to cars backed up for a 1/2-mile, frayed nerves, people arguing over parking spots, and trashed bathrooms. Ugh.

According to a park volunteer, early tourist attractions increased the park’s popularity and one of the biggest was Firefall which occurred 100–150 times each summer. Up at Glacier Point, men would take a half-cord of bark, build it into a massive fire, and then slowly shove it off the edge to fall to the valley below. When properly executed, the falling embers looked like continuous lava flow for 10–15 seconds. Firefall was shut down in 1968, in part due to damage to the meadow where crowds would gather for the evening spectacle.

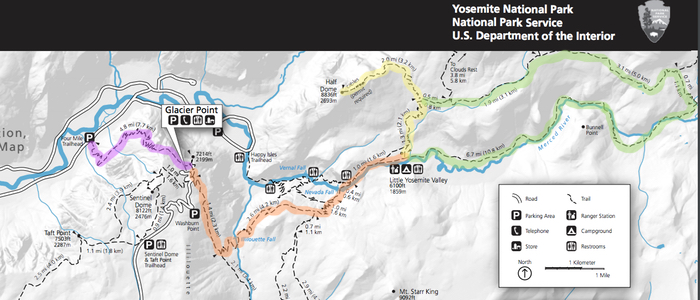

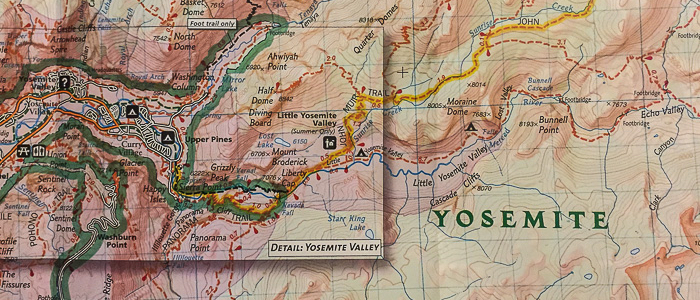

Yosemite doesn’t need Firefall to draw visitors; its raw beauty is lure enough. We had four days to explore the park, and each hike sparked thoughtful conversations. Here’s a Yosemite Valley trail map, reproduced below with highlights added for each of our hikes:

Four Mile Trail: Are our parks too parky?

Four Mile Trail is 4.8 mile trail from the valley up to Glacier Point, so 9.6 miles total for the out-and-back. With 3200 feet of gain, this trail is up all the way up, and down all the way down. The original trail, completed in 1872, was four miles, but it was improved and lengthened to remove steeper sections.

This hike was one of many where we debated if our national parks are too nice, too accommodating, and have too many amenities, resulting in visitors who have a false sense of security, are ill-prepared, and make poor decisions. Karen suggested that calling them “parks” might be part of the problem with the connotation of playgrounds, ballfields, and tidily trimmed grass. On the hike down - true story - we rounded the corner to find a park service worker sweeping the trail. With a big push broom. Half way up Four Mile Trail. Crazy sight! In the park’s defense, she’d been doing trail maintenance and the trail was quite slippery with sand over stone. Still, the timing was hilarious and the icing on Karen’s “parks are too parky” cake.

We hiked up and back in 5 1/2 hours, but some folks take a tour bus up to Glacier Point and hike down; check the bus schedule for prices and seasonal hours.

Panorama Trail: Longer hikes = Fewer people

We backpacked the Panorama Trail from Glacier Point, past Illiouette Fall and Nevada Fall, then picked up the John Muir Trail to Little Yosemite Valley (LYV) Campground. The 6.4-mile hike took us about 4 hours and provided almost continuous expansive views of Yosemite valley and beyond. Hikers clumped up at Glacier Point and Nevada Fall, but we found solitude in between.

What constitutes a “long” hike is subjective, but generally, the further you go the fewer people you’ll see. If you crave silence and peaceful wilderness in Yosemite, load up a daypack with the 10 essentials and get beyond the 30-minute hiker zone. Better yet, grab your backpack and trek into the backcountry.

Ranger Turner, who gave us a peppy “Responsible Hiker 101” talk while waiting in line for a Half Dome permit, encouraged us to get away from the closer high-use spots and dive deep into the backcountry. But - big but - do so responsibly. In my trail journal I noted “Ranger Turner brooks no nonsense! He will very happily crush our dreams and escort us out of the woods for any and all infractions because we need to be good stewards of the environment for ourselves and future generations. And to protect our friends the bears.” You can read Yosemite’s wilderness regulations before setting out, though it’s much more entertaining to hear it straight from Ranger Turner.

Note that the Panorama Trail is quite popular and could be used as a launchpad to more remote trails. To really get away, turn south at a junction, or keep heading east/northeast past LYV campground.

There are bear lockers in the Glacier Point parking lot; it’s important to remove all smellables (food, toiletries, etc.) from the car before setting out.

Half Dome: Make like a Boy Scout and Be Prepared

Many dream of climbing Half Dome and it was certainly a highlight of my Yosemite trip. It’s surprisingly accessible, but don’t equate “accessible” with “easy”. The climb takes preparation, honest self assessment, and personal responsibility. On our trek, we saw people that were exhilarated and uplifted, and many others who were exhausted and terrified.

I wrote this article detailing what to expect, how to prepare, and what to take on a Half Dome hike. For us, Half Dome was just the beginning: We camped overnight at LYV campground, set out for Half Dome at 8:45am the next morning, climbed Half Dome, went on to hike the Moirane Dome Loop, and returned to the LYV campground at 6:20pm; a long but amazing day. We hiked 18.2 miles all in, but if just hiking from LYV campground to Half Dome and back, it would have been about 7 miles total.

Moraine Dome Loop: Burn baby burn

I’m not sure if this loop has a name. It starts on the John Muir Trail loosely following Sunrise Creek, cuts east towards Echo Valley, and then loops back to the south and west along the Merced River through Little Yosemite Valley. Moraine Dome stands in the center, so we’ll go with that!

Whatever the name, it’s a gorgeous hike that starts and ends in old burns. In between the burns we encountered granite slabs, a bouldery wash, forested paths of glowing aspen and sweet-smelling pine, and a rocky canyon with bridges criss-crossing gushing streams. Loved the variety!

One couple we passed wasn’t thrilled with tromping through miles of burned forest, but after multiple discussions stressing how crucial fire is for forest health, I viewed the blackened landscape through rose colored lenses. In a Glacier Point nature talk I learned that Yosemite currently has 150–200 trees per acre where there should be just 20–25 per acre. Why the proliferation? For much of the 1900s, forest managers enacted a policy of total fire suppression to protect people, property, and valuable timberland.

As it turns out, we need fire to burn undergrowth, thin trees, and return nutrients to the soil. Prior to the suppression policy, low burning, slow moving forest fires would do their magic on a natural ~30-year burn cycle. Without regular burns, however, underbrush has grown thick, and trees have become overcrowded and stressed as they compete for nutrients and water. Gone are the days of controlled forest fires. In their place, we have raging wildfires that are difficult to contain and extinguish.

In one particularly funny moment (to me), our park volunteer proclaimed that “…once a wildfire starts there’s nothing you can do but watch it and call the media.” Really?! Karen’s reaction was priceless. Context: Karen is a wildland firefighter. Apparently she just stands around a lot with a phone in her hand (!).

We camped at the LYV campground for two nights, which is “little boy backpacking” according to Ranger Turner. I see his point; the LYV campground is vast, almost like a tent city, though much quieter than we thought it’d be given the numbers. If I go back, I’ll surely hike beyond the campground and find a secluded spot in the woods - we passed a number of good options on the hike.

On the plus side, LYV campground provides shared bear lockers and community firepits. The Merced River is close by to fill and treat water, and soak tired, sore feet (bliss!). After the Half Dome climb, we hiked 12.9 miles on the “Moraine Dome trail” in 5.5 hours; to truly make it a loop starting and ending at the LYV campground, add 1.3 miles for 13.4 miles total.

A few other notes: The first two nights in Yosemite, we stayed up at Porcupine Flat Campground and commuted down to the valley, a one-hour drive each way. Porcupine Flat has no water so we filled in the valley, once at the Lower Pines Campground (there’s a bottle fill outside the bathroom near the entrance) and once at Degnan’s drinking fountains. Though nothing fancy, it was a treat to shop and eat at the Curry Village Pavilion. We bought firewood there, and as cold as it was, that $5 was probably the best ROI of the whole trip.

So are we loving our parks to death? Perhaps. But if we all do our part, there may be hope yet: tread lightly, be informed and prepared, adhere to wilderness regulations, and follow the old maxim to "Leave a place cleaner than you found it."

Yosemite is wildly popular for good reason - it's a sight to behold and possesses a magnificence and expanse that somehow fills the senses and soothes the soul. If you can wrangle the time, visit off-season and explore beyond the main high-use areas. Like me, you may fall in love; the Sierras are calling even now.

This article is one of many written about a 3-week road trip spent hiking and camping in the Eastern Sierras and Death Valley. To see all articles, check out this trip summary.